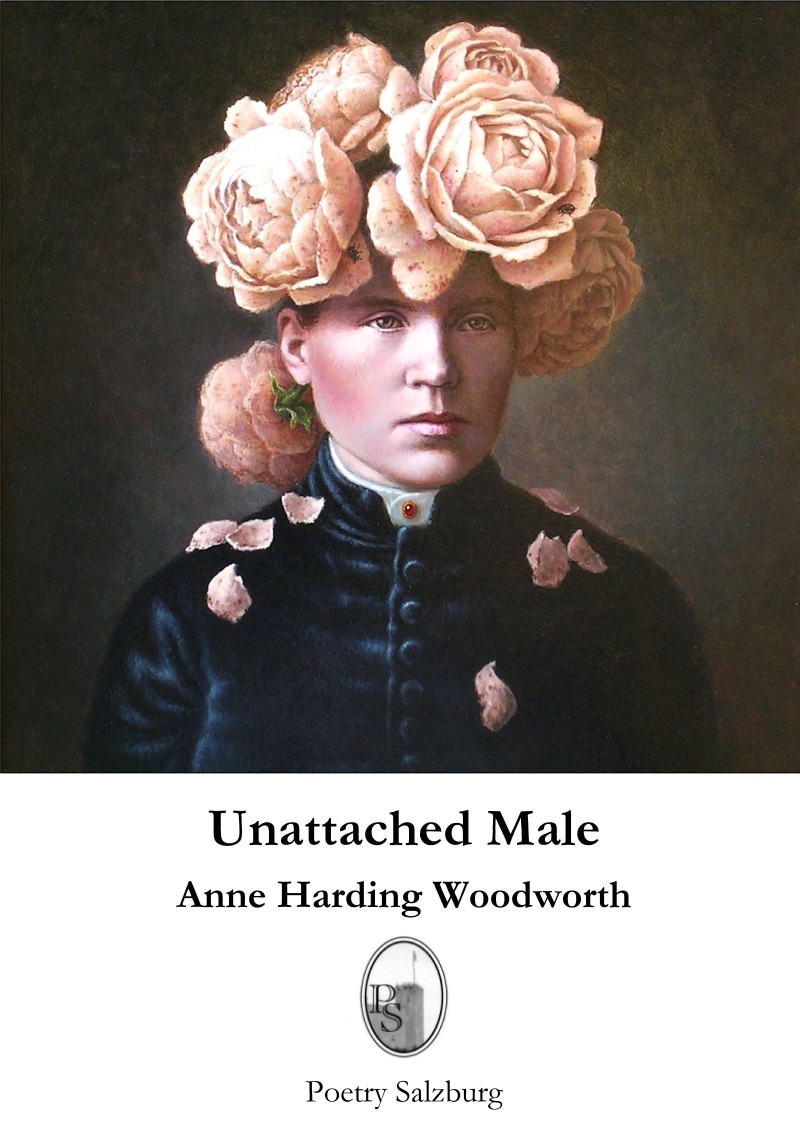

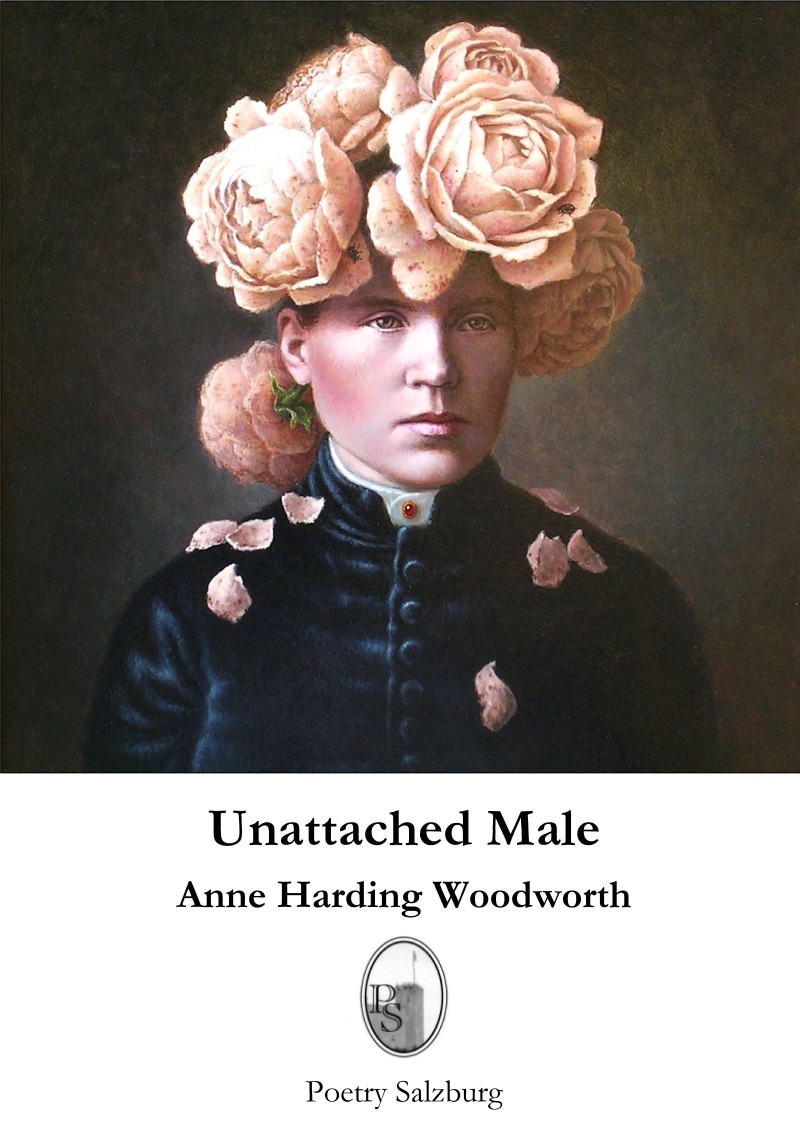

| Anne Harding Woodworth

Unattached MaleApril 2014. 84 pp. ISBN-13 978-3-901993-45-9

£9.50 (+ 2.00 p&p), €12.00 (+ 2.50 p&p), US$ 16.00 (+ 3.00 p&p)

"In Unattached Male Anne Harding Woodworth 'plays' her poetry as a virtuoso musician plays an instrument: with acrisp, authoritative, confident touch that never leaves the reader (or, better, the 'listener') in doubt. Whether intoningimages of music, art, myth, or family history - even the banalities of everyday life raised to eternal truths - hersis a vigorous poetry, free verse at its best, expertly tuned to the deeply personal but never mawkish sketches she creates.Verse free, but never helter-skelter or arbitrary, in which every word is the 'note juste' in the melodic, harmonic,and contrapuntal whole. A poetry that richly satisfies ear, mind, and heart." Norman R. Shapiro

"In Unattached Male Anne Harding Woodworth makes palpable an astonishing array of male lives. As the titleindicates, she focuses specifically on the terrible separateness of men and how that has played out in particular livesin particular eras. The conclusions she draws are not so much conclusions as moments gently held in the hands of wonderment.What is at work here is compassion that stares down the spectacle of pity, that moves through much quiet and unquietsuffering that affects the lives of men - and women - each day."Baron Wormser |

Order copies of Unattached Male via PayPal:

Table of Contents

Excerpts from Unattached Male

Unattached Male

My great-grandfather was not to be touched,

or so they said. But those who knew the stories are gone,

like him and all the others buried on the hillside

near Utica, detached from the family tree,

like the fancy collars he wore, separated

from the shirt, washed less, starched more,

like a crisp bill. Money was his only friend -

that myth remains - but he lost it all in '29,

not long after he'd sat for a photograph,

sepia portrait in a golden frame over the mantel.

Once, I yearned to touch his skin

to see if it were mine, to follow the creases

of his forehead with my index finger, his big ears,

and to smooth his white hair. But he eluded me

like all ancestors, and that's the good fortune

of anyone who wants to be free. The portrait

stops at his waist. Perhaps he has no legs.

He's attached to nothing, will stay over the mantel,

until they've forgotten even his name.

To a Father

You're proud of the explosives around his midriff.

It comforts you under the buttons of your shirt,

soothes you, that he was brave enough to kill himself

and the enemy you share no prayer, no words with.

There's no need for translation. The Tower of Babel

has all the confusions: you sift stones of colors

from your garden of fruits, while Crusader fortresses

of boldly hewn stone glisten in the desert.

You've watched a crowd stone a woman to death.

Silence after an outburst of joy ensures the secrets

of your place, where loss becomes gain around you.

I transliterate stone into hajar but I don't know the word.

That's how far away I am from you.

So I watch you and ask beyond language:

how is it that a father made childless

can be the happiest man on earth?

André Kertész, Photographer

Disembodiments stalked him wherever he was.

Not the Eiffel Tower - the bridge that severed it.

Not the fork - its shadow on the table.

He couldn't go out any more, was slowing down

so he looked out his window at roofs and faded shutters

until he turned inward and became the warrior's prosthesis -

detached and splayed within a dark closet,

while naked women undulated darkly in his fun house mirrors.

Whose outsized midriff is that? Whose bulbous calf

is curving like a spoon? Whose arm within the paddles

of a kitchen fan? And where do all the bodies sing, or sleep?

At last he stayed inside for good and looked

toward warm enclosing chairs, and at the end

he laid his head against the crocheted antimacassar.

The Loneliness of Making Lace on a Computer

A bank of screens lights up the faces,

even his, fifth from the door,

in the darkened room,

where they design the stems and flowers,

leaves that will one day meander

through open eyes and into o's

in ways only machinery understands.

He creates a nightgown hem,

a neckline, and panty waists -

tats himself into outstretched arms

of someone who will wear his lace

more delicate than a baby eel.

He hears her voice, profane and strange,

and no one catches on

he's making love to diaphane.

Read more about Anne Harding Woodworth

Send an e-mail to order this book